Introduction – Page 2

Every fanbase has an idea of itself that it projects to the world, and through which reality itself is channeled. Whatever fits this image is emphasized. Whatever doesn’t is ignored. The Steelers are Blue Collar. The Flyers are the Broad Street Bullies. The Cubs are Lovable Losers. And the Mets? The Mets are Amazin’.

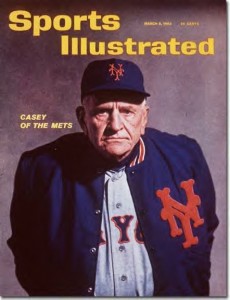

This truncated adjective was first coined by Casey Stengel, steward of the Mets’ earliest editions, to describe their historical ineptitude. Those teams seemed to hail from another planet, finding ways to lose never before conceived, let alone executed. Their new fans—comprised largely of lost souls abandoned by the Giants and Dodgers’ moves to California—couldn’t care less that this new team was lost without a map. This was, perhaps, the only approach to take for a fanbase that had to define itself in terms what distinguished themselves from the Yankees, who were then the living embodiment of Success. So fans subsumed the Mets’ innovative brand of awfulness into their idea of what the Mets should be.

This truncated adjective was first coined by Casey Stengel, steward of the Mets’ earliest editions, to describe their historical ineptitude. Those teams seemed to hail from another planet, finding ways to lose never before conceived, let alone executed. Their new fans—comprised largely of lost souls abandoned by the Giants and Dodgers’ moves to California—couldn’t care less that this new team was lost without a map. This was, perhaps, the only approach to take for a fanbase that had to define itself in terms what distinguished themselves from the Yankees, who were then the living embodiment of Success. So fans subsumed the Mets’ innovative brand of awfulness into their idea of what the Mets should be.

This phenomenon was captured by the great Roger Angell, who penned one of the very first studies of the Mets and their fans in his 1962 New Yorker piece, “The ‘Go!’ Shouters.” Angell took a trip to the Polo Grounds to observe people who felt compelled to shout, sing, and create signs celebrating a team that, on the surface, possessed absolutely nothing worth celebrating. The 1962 Mets were an epically awful team, and yet a dedicated group of maniacs gathered at a crumbling old ballpark to scream their lungs out for the team’s modest accomplishments. A lesser writer would have dismissed these as expressions of either irony or delusion. Angell saw something else entirely.

This was a new recognition that perfection is admirable but a trifle inhuman, and that a stumbling kind of semi-success can be much more warming. Most of all, perhaps, these exultant yells for the Mets were also yells for ourselves, and came from a wry, half-understood recognition that there is more Met than Yankee in every one of us.

This redefinition of what deserved to be cheered remained intact until 1969, when the Mets stunned the world by coming out of nowhere to win their division, a pennant, and finally a championship. The definition of amazin’ was then expanded to include the sublimely unlikely, the laughable underdog turned king of the hill. Thereafter, it seemed every instance of success for the Mets would involve similarly unlikely scenarios, whether it was their late season surge from worst to first in the “ya gotta believe!” season of 1973, or their unbelievable come-from-behind playoff victories in 1986.

Wonderful or horrible, the Mets must be amazin’. When the Mets win, they win by impossible, insane means that would be written out of the hackiest Hollywood script. When they lose, they snatch defeat from the jaws of victory in soul-crushing fashion. These are the outcomes a Mets fan will accept. Mets fans do not know what to do, really, with an ordinary defeat or a tidy win. Not every single game the Mets play has an unlikely outcome, but this inconvenient fact is almost irrelevant when a sizable portion of their fanbase feels like every Mets game fits into one of these molds.

Prime example: The 1986 Mets won 108 regular season games, making them one of the most dominant teams in baseball history. But if you watch the highlight video from that season (A Year to Remember, daily viewing for me as a child), you would think the 1986 Mets had to scrap and struggle and fight their way through every victory. The video emphasizes all of the toil and displays virtually none of the ease with which they destroyed the rest of the National League that year. It contains gritty touches such as a musical montage of Wally Backman and Lenny Dykstra getting dirty on the basepaths to the tune of Duran Duran’s “Wild Boys.” A narrator refers to the two scrappy players as “partners in grime,” as if slap bunting and headfirst sliding were the reasons the Mets were so great in 1986. A montage like this fulfills the psychic needs of Mets fans, even when looking back at a team that leveled the competition. Something in fans’ DNA needs the Mets to not only win, but to overcome an insane amount of adversity and accumulate a lot of uniform dirt while doing so.

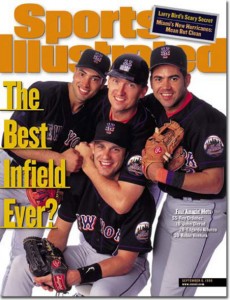

Knowing this helps you understand why 1999 may be the “most” Mets season in franchise history. The team had a largely anonymous pitching staff, a contentious outfield full of various stripes of misfits, and a roster that contained two former replacement players. The flashiest part of their game came from their stellar infield defense, prompting Sports Illustrated to adorn a cover with John Olerud, Edgardo Alfonzo, Rey Ordonez, and Robin Ventura while pondering the question, “Best Infield Ever?” They were helmed by a manager who always seemed on the brink of being fired for some offense or another, at constant odds with other skippers, umpires, his general manager, ownership, the media, and nearly everyone else in the game of baseball (and some out if it, when he could find time in his schedule to piss them off).

Knowing this helps you understand why 1999 may be the “most” Mets season in franchise history. The team had a largely anonymous pitching staff, a contentious outfield full of various stripes of misfits, and a roster that contained two former replacement players. The flashiest part of their game came from their stellar infield defense, prompting Sports Illustrated to adorn a cover with John Olerud, Edgardo Alfonzo, Rey Ordonez, and Robin Ventura while pondering the question, “Best Infield Ever?” They were helmed by a manager who always seemed on the brink of being fired for some offense or another, at constant odds with other skippers, umpires, his general manager, ownership, the media, and nearly everyone else in the game of baseball (and some out if it, when he could find time in his schedule to piss them off).

In 1999, the Mets danced with danger at every turn, pulled themselves from the brink more than once, stared death in the face and all but dared it to claim them. It was a season marked by ridiculous comebacks, controversy, and you-couldn’t-make-it-up outcomes. They were like a band so great but volatile they were doomed to make one transcendent album and never be heard from again.

From a pure political standpoint, it would have been impossible for the Mets to not try to improve on 1999 after going so far in the playoffs. The media would have ripped them to shreds, to say nothing of fans who’d gotten a taste of the postseason after a long drought and longed for more. There were also the dual factors of General Manager Steve Phillips, who was perpetually looking to make Big Splashes, and then-co-owner Fred Wilpon, who, bristling under the contention that the Mets were New York’s “little brother” team, was eager to enable him. All of this made a quiet offseason a near impossibility. And yet, in retrospect it seems any attempt to make something better than 1999 was foolhardy at best. How could even a World Series Championship compare to what the Mets had achieved spiritually in 1999?